ommx:

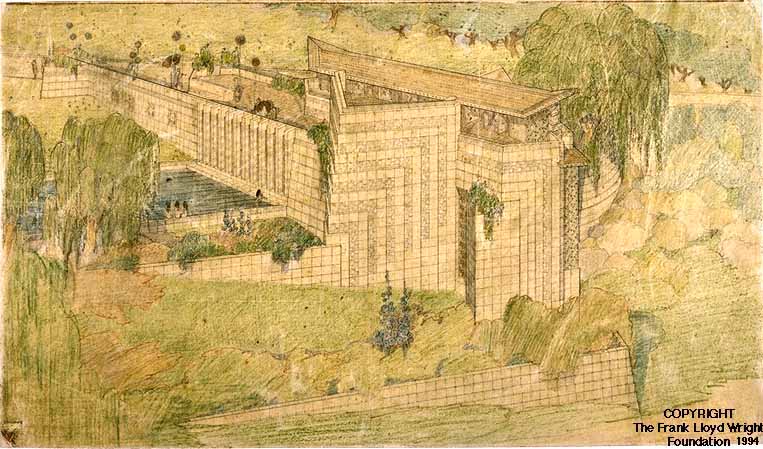

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hollyhock House

flw

ommx:

Frank Lloyd Wright, Hollyhock House

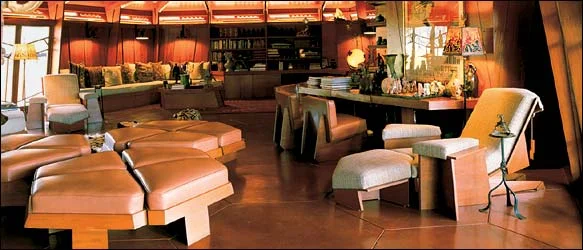

Inside Wright’s Imperial Hotel, Tokyo

#ARCHITECTURE #ARQUITECTURA #ARQUITETURA #SKETCH

Frank Lloyd Wright

05.11.2013.22.02

http://arquitecturamashistoria.blogspot.pt/2011/01/croquis-maestros-el-gran-artesano.html

frank lloyd wright’s hollyhock house, 1921

(aline barnsdall residence)

living room + fireplace

4800 hollywood boulevard

photos by marvin rand, 1965

via: decaying hollywood mansions

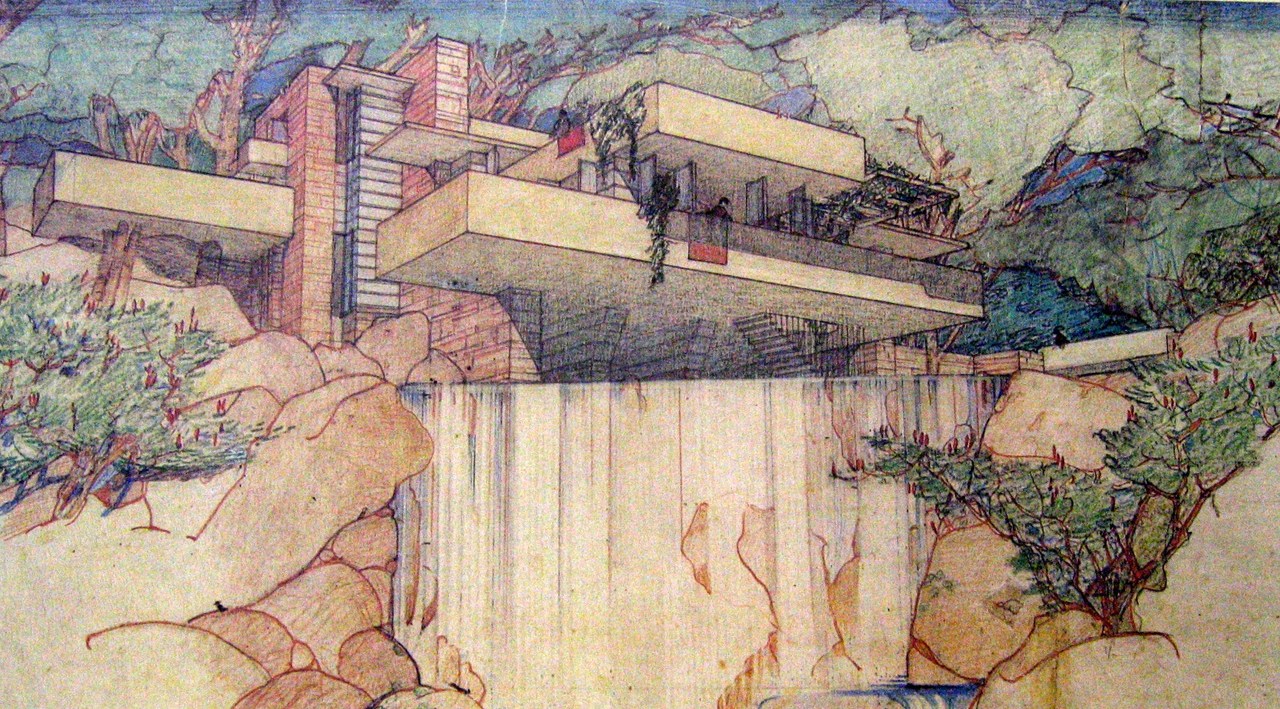

“Wright’s design of 1923 responded to the expansive qualities of the Doheny site, respected local vegetation, and accommodated the automobile in both spatial and architectural terms. It was nothing less than an idealized prototype for what American suburbs might have become, but did not. As surviving perspectives demonstrate, buildings, roadways, and plantings are conceived as an integrated totality; it is the vision of the suburb as one structure.

Roadways depicted as powerful visual elements appear to terrace the hills, providing a unifying pattern. Developed in the manner of viaducts, they bridge intermediate ravines on gracefully arcuated spans or massively embank the steep terrain. Walls defining these roadways extend to become walls of the houses themselves.

Numerous roof terraces broaden the horizontal planes of the connecting roads, amplifying an architectural image of vast scale. Both roads and houses are clustered in ways that structure the site by selectively shaping and retaining the natural slopes. The more fragile segments of valleys and the steepest slopes are left largely untouched, but are joined in the full composition to achieve an effect of extraordinary unity.”

-LOC

“Intended as a neighborhood kindergarten, The Little Dipper was partly built on its Olive Hill site before Aline Barnsdall, impatient with cost overruns, halted construction. Of interest as it relates to the Doheny Ranch project, the drawing demonstrates a clear advance in angular planning. Diagonal segments of the plan are smoothly integrated into bridging elements that link terraces and pools into a single, persuasive composition.

Office of Frank Lloyd Wright Graphite and colored pencil on tracing paper, ca. 1923

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona (24)”

My favorite image from the ApluD exhibit “Los Angeles, Neverbuilt”

Frank Lloyd Wright’s proposal for Doheny Estates.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Auldbrass Plantation, Beaufort County, South Carolina - New York Times article about the restoration

Chicago’s landmark The Rookery. Designed and completed by Burnham & Root in 1888, the lobby was remodeled by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1905.

Taliesin Architects HQ

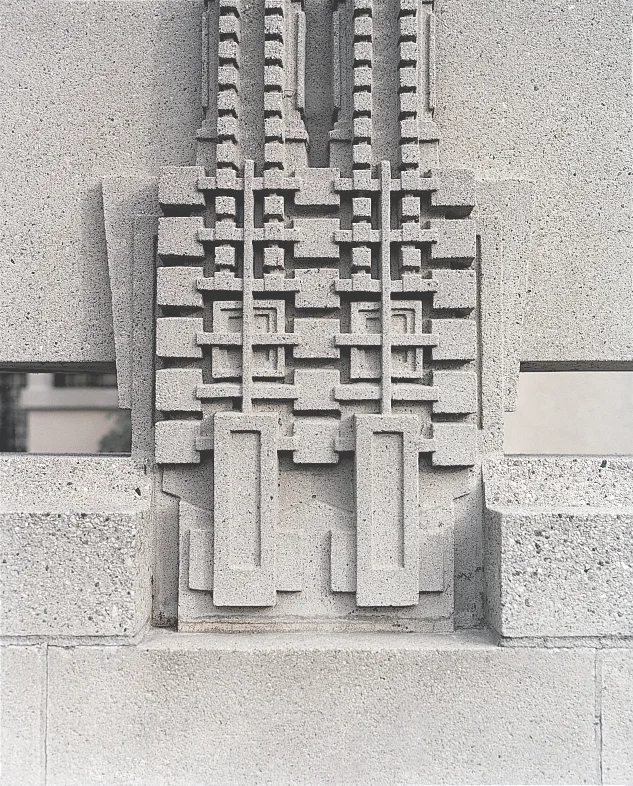

“La Miniatura,” Frank Lloyd Wright’s Millard house (1923), Pasadena, California

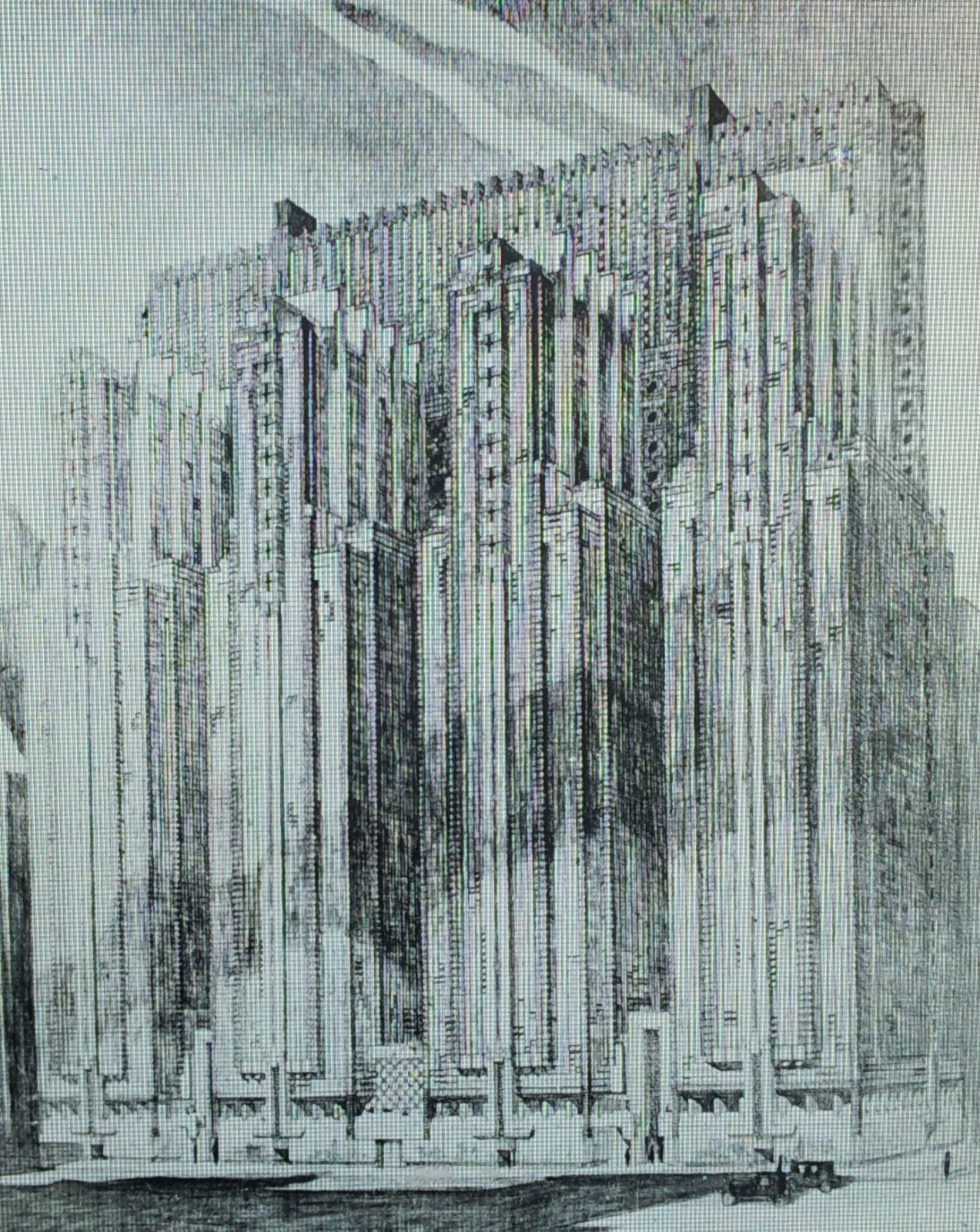

Plans for Frank Lloyd Wright’s National Insurance Building, 1924, Chicago.

Meant to have been built on North Michigan Ave at Chicago Ave, the glass and copper facade proved to be too expensive for developers. This building is often cited as the greatest FLW structure that was never built.

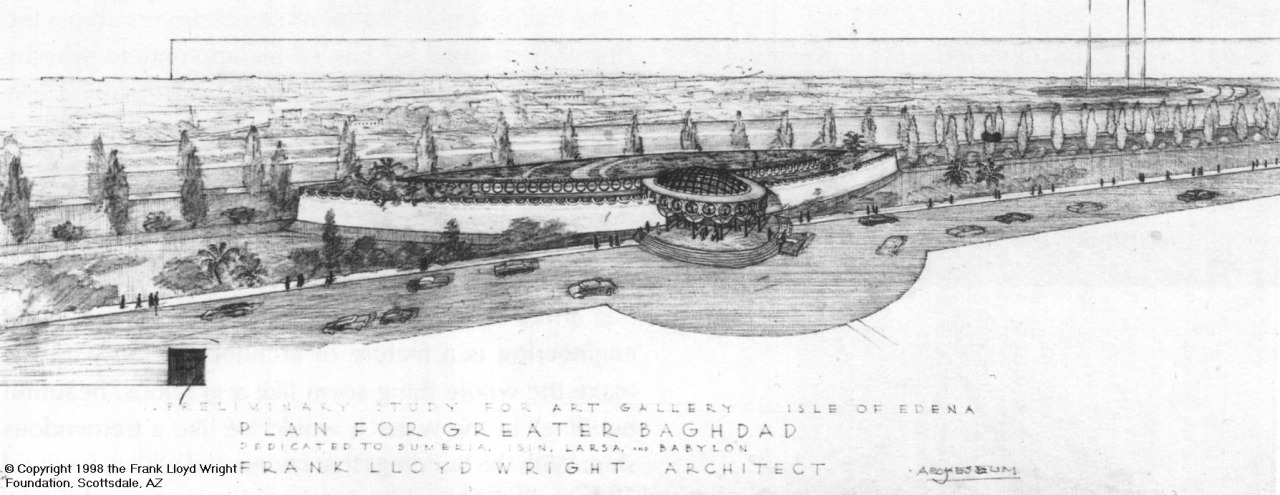

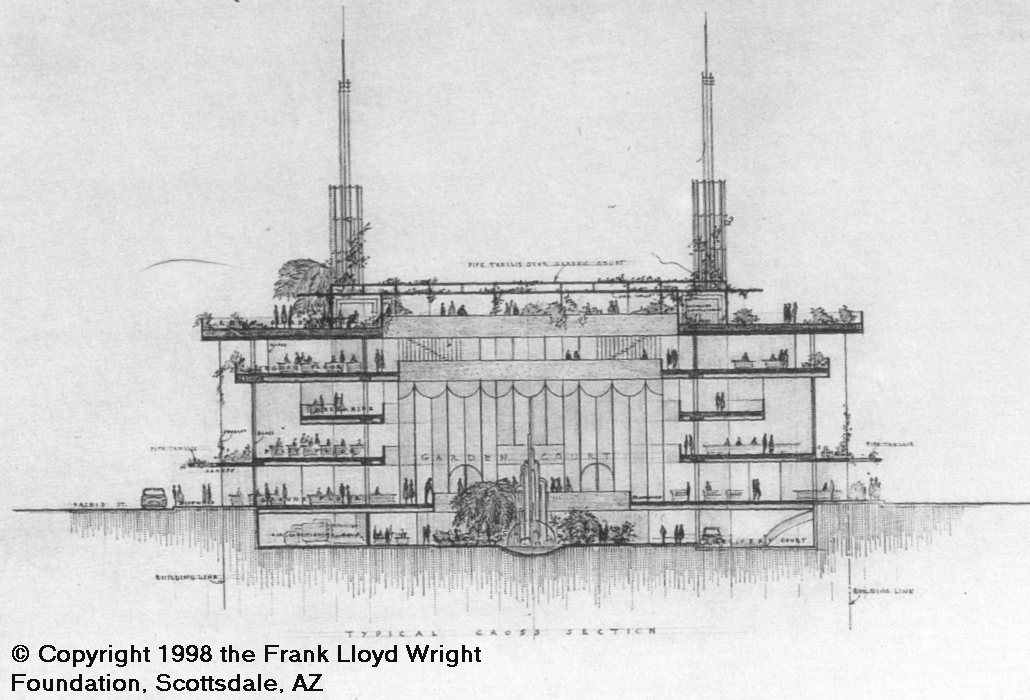

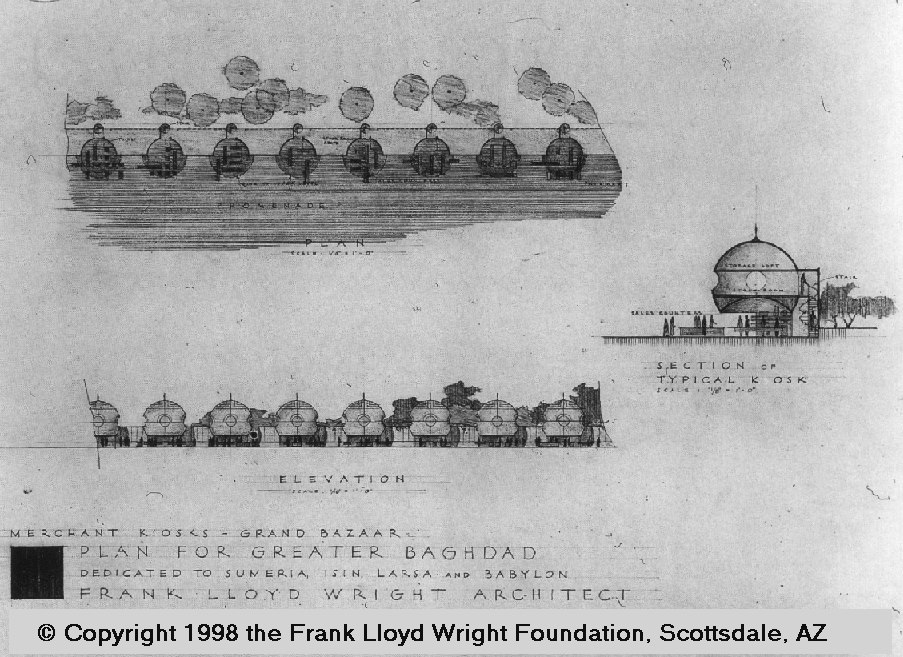

Plan for Greater Baghdad - Frank Lloyd Wright

“A great culture deserves not only architecture of its time, but of its own”

Wright’s 1957 plan distilled an imagined memory of the ancient Abbasid city and went back even further to one of the oldest myths of mankind, the story of Adam and Eve. Quite apart from the political events that scuppered it, it was dismissed by modernist commentators at the time as an anachronistic phantasmagoria. But Mina Marefat persuasively argues that Wright’s work stands as a valuable symbol today, by showing profound respect for the very cultural heritage to which the west can be hostile. ‘The functions of an opera house, a civic centre and a university were clearly modern ones,’ she says, ‘but Wright gave them forms that linked them to the past and imbued them with didactic cultural messages, collective images shared by both east and west.’ Though the realization of Wright’s project would now be less imaginable than ever, it’s worth pausing to remember than when America’s greatest architect drew up a blueprint for Baghdad it was not chauvinistically western, nor an American attempt to destroy Iraqi culture. It was made in a spirit that future architects for the city might do well to study.

Architecture by Frank Lloyd Wright at Florida Southern College

Lucius Pond Ordway Building, 1952

ARCHITECTURAL COLOR SKETCHES | 1181 | FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT | SOURCE

![alapiseira:

Plan [162]

archimaps:

Wright’s plan for the Willits House, Highland Park, Illinois](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54e6c8ece4b0663b4a76f755/1437625816346-W95M00TNUJ53TT4OFBY0/image-asset.jpeg)

Plan [162]

Wright’s plan for the Willits House, Highland Park, Illinois