Part1: Trip to Casa de Vidro (1951) by Lina Bo Bardi, Sao Paulo, BR, photos TDeVoss 2013

interiors

/

T DeVoss.

Deasy Penner Office Interior - Venice, CA

/

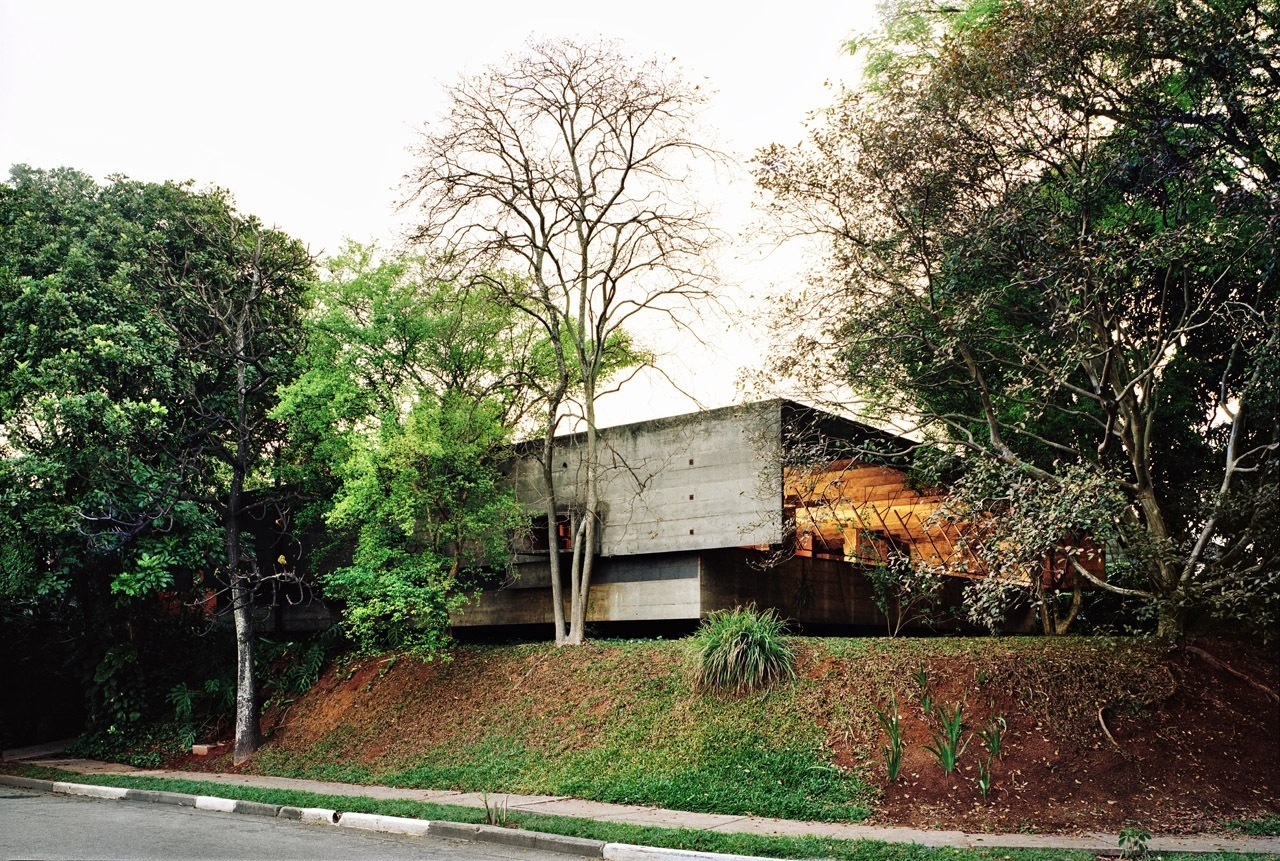

Paulo Mendes da Rocha | Casa no Butantã, the architect’s own home. Brasil, São Paulo, 1966.

/

/

/

/

/

/

Omotesando Night Club Research Studio | Jiannan Liu Tingwei Xu

(via Arch2O.com)

/

Madada Mogador - Essaouira, Morocco

Ideally located on the shores of the Atlantic, Madada Mogador is a luxury riad where intimacy and silence invites you to relax. Build in the spirit of a loft, the riad features 4 bedrooms on the first floor and 3 more on the beautiful terrace, from where you can enjoy breathtaking views over the fishing port and beach.

Chic Modern Living Rooms /

Dreamy Nook Beds /

/

/

/

/

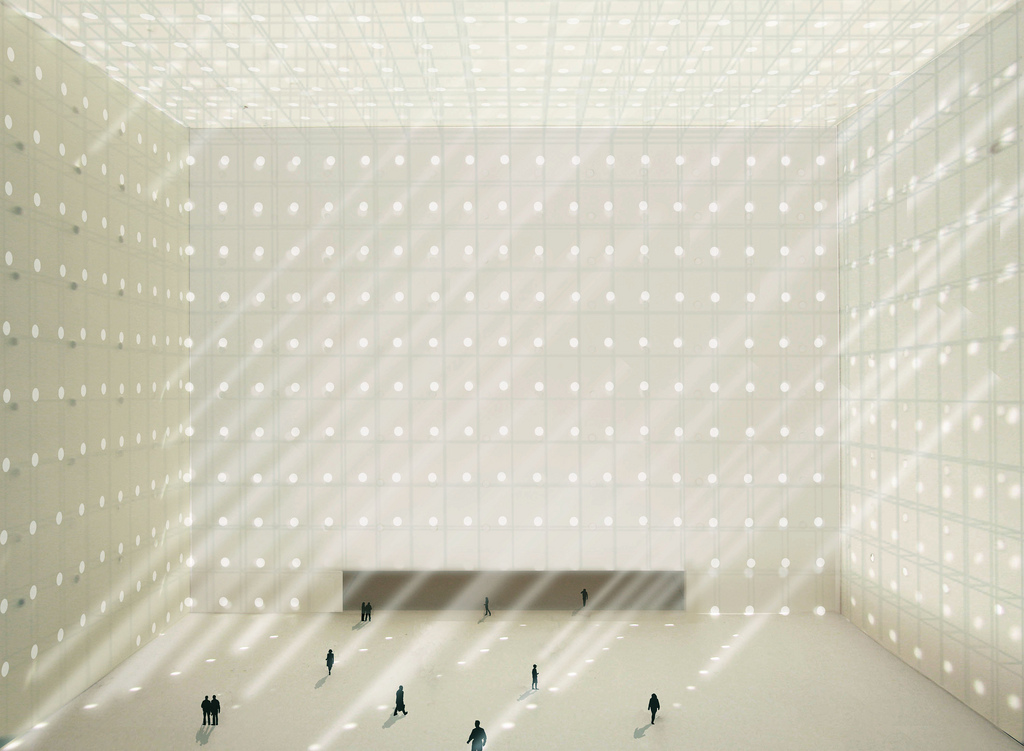

Alberto Campo Baeza with Paulo Henrique Durao - Proposal for the Porta di Milano, Milan.

“We would like to build the most beautiful space in the world. The most luminous. The most fascinating. With just the mechanisms of Architecture. The simplest, the clearest, the most beautiful… It would be like a cloud. The most mysterious space, the most surprising, the most exciting.”

Cozy Rustic Attic Bedrooms /

/

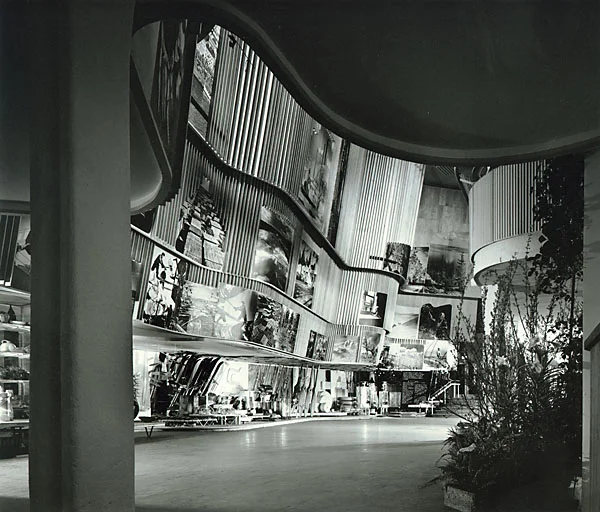

Alvar Aalto’s Finnish Pavillion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair

For the pre-Information Age society of the late 19th and early 20th centuries it would be hard to overstress the significance of the World’s Fair. At a time before the Internet, television and commercial air travel made the world a seemingly smaller place, foreign countries often remained largely mysterious to each other, especially those that were oceans apart. The World’s Fair provided a showcase for each country to express its true nature by displaying its customs, people, industry, craft, and architecture. The pavilions were often the first experience visitors would have with a country and the need to summarize the experience of entire nation in one building provides a daunting task for the architect. For Finland’s entry to the 1939 World’s Fair in New York Alvar Aalto was selected for the challenge.

The New York Fair came at a particularly important time in our world’s history. America was just rebounding from the Great Depression while World War II loomed imminently in Europe. The precarious situation of world affairs was slightly offset by the potential of groundbreaking new technologies (i.e. television), which were featured prominently at the fair. The fair strove to evoke a feeling of hope and optimism for the future in all its buildings, an effect that most architects chose to represent through the playful geometries of Art Deco or the machinated forms of Modernism. Aalto’s pavilion achieves the uplifting effect but through unconventional and amorphous means, successfully creating “one of the twentieth century’s most astonishing interiors.”1

Due to financial constraints, Finland was only able to rent a narrow, rectangular box-shaped building for its pavilion.2 The exterior shape already having been determined, Aalto focused on maximizing the interior space through the development of “a free architectural form.”3

The program called for separate areas to showcase the physical beauty of Finland, its people, its industry, and its produce hence the pavilion’s motto: Maa, Kansa, Tyoe, Tulos (Land, People, Work, Products). Aalto spaced these areas over four floors but consciously tried to “bring together these elements and create a harmonious whole.”4 To unify the interior space Aalto employed an undulating wall of randomly spaced vertical wood batten boards and plywood, opened periodically to views (photographs) of Finland. The effect for the visitor is of walking through an architecturally abstracted Finnish forest. The wall’s shape conjures up thoughts of Finland’s most famous natural feature, the aurora borealis, but also of the curving shape of a lake edge. In both its materials and its form the wall bears the organic mark of Finnish culture, providing an appropriate signature element to the pavilion.

A visitor enters the pavilion and walks into a low-ceilinged anteroom 15 feet long by 5 feet wide that serves as an information counter and greeting area (number 1 on the above plan). Immediately one’s eyes are swept left and upward following the curving shape of the wall. From the entrance anteroom the view of the main space is partially obscured by plantings and the administrative office (2). This encourages the visitor into the large central area embraced by the curvilinear wall and towards the standing glass cabinets that showcase Finnish glassware (10). Many of the pieces exhibited in the wares section are those of Alvar and his wife Aino, the wavy shape again informed by Finland’s many lakes.

Proceeding clockwise the visitor comes to the furnished rooms section of the pavilion (9). Here the visitor can see how a typical Finnish house might be decorated. Following the flow of the wall carries the visitor to the area that celebrates Finland’s industrial products. Everything from wooden airplane propellers, to skis, to giant cheese wheels are on display. Its organization is “like a country store.”5

“An exposition ought to be what it has been since its origin: a bazaar where all kinds of heterogeneous objects are displayed indiscriminately whether they be fish or fabrics or cheeses. For this reason I’ve looked for the greatest possible concentration, a place stuffed with juxtaposed, superimposed merchandise, industrial products and groceries separated only by a few centimeters from each other. It was no easy task to bring together these elements and create a harmonious whole.”

– Alvar Aalto6

Here, at the industry exhibit, the visitor feels the whole height of the pavilion, the curving walls projecting farther into the central space with each rise to the next floor. The battens seem to hover as they lean into the space. From this vantage point, the viewer looks up into the spaces between the vertical plywood boards, draped from the wall like the vertical streams of excited atoms falling through the atmosphere. The visitor is inclined to move into the central space to look at the majestic curving wall and enjoy the large photographs that pierce the arrhythmically continuous battens.

The photos continue the theme of the pavilion; ‘Country, People, Work,” and would certainly have impressed the visitors who were not used to seeing photographs at this large size. Visitors can view the photographs comfortably from the ground floor thanks to the tilt of the auroral wall.

The top two rows show scenes of the Finnish landscape, the people and their lives, and the bottommost layer show scenes of labor.

On the pavilion’s opposite side is an open tourist information center and area for the promotion of the Helsinki Olympic Games of 1940 (see image below). These areas Aalto furnished with Artek tables and chairs of his own design.7

Continuing through the building takes the visitor up a few shallow stairs to a landing. In front are the exit doors, and to either side are sets of stairs to different sides of the second floor. The wall around the exit doors is decorated with carefully arranged discs of birch wood. Aalto originally conceived of the discs to cover the entire wall in varying sizes (as seen in the section below) but opted instead for a more geometric organization where the circular discs defined a square grid pattern. The staircase to the left rises behind the curving display wall but follows its shape. On this floor the visitor is greeted by the exhibition area of the Finnish economy and culture, complete with a scale model of an ideally planned Finnish community (numbers 15 and 16). The visitor continues through the exhibit gently urged on by the flowing form of the wall they were just on the opposite side of. The visitor circles back around the pavilion to a mezzanine above the tourist information center where the restaurant is located (12).

Suspended above the restaurant eating space is a projection booth, clad in the same batten boards as the curving wall. Diners in the restaurant can see moving images of Finnish culture projected onto screens imbedded in the wall by the exit. The balcony railing continued the wood theme by using bent birch planks, slightly cantilevered over the court in a shallow, positive parabolic arch. Finland’s deep connection with nature is perhaps most evident in a huge aerial map mounted on the wall above the restaurant and opposite the curved wall. The map, with its archipelago of wilderness islands, lets the visitors understand just how intrinsic the connection must be between Finns, forests, and their 60,000 lakes. From the restaurant, visitors take a spiral staircase down towards the exit and a retail area (7) featuring Finnish goods and souvenirs. The circulation through the building is complete and well-defined despite being entirely free-flowing. Aalto turns a rectangular box into an area to meander through in an unconventional but purposeful way. Every surface is either decorated by wood or used for photographs and so the entire composition maintains a connected and nature-driven feel. It is only natural then that Aalto continue the theme in his ceiling.

The ceiling features a series of rectangular skylights that follow the shape of the curving display wall. Hanging from the ceiling are large and small airplane propellers which act as fans. The elegant shape of the propellers not only circulates air, but also breaks up the light that filters through the skylight, creating a dynamic and comfortable environment from improvised materials.

The pavilion exudes a feeling of movement and vitality in every detail. Aalto understands that the role of a pavilion at the World’s Fair is to convey the essence of a country in as pithy a way possible. Since the fair offers so many varied amusements, the average visitor, in all likelihood, will probably stroll through the entire pavilion while barely stopping to contemplate all they see. It becomes the responsibility of the architect to bring forth certain thoughts and feelings from people on the subconscious level while meeting the challenging primary requirements of the project.

“After all, not even objects in themselves can give a picture of a country; in its most convincing form, that can only be done by the atmosphere they create as a whole, in other words only the whole that can be apprehended instinctively.”

– Alvar Aalto8

The curving forms are architecturally interesting but also reference the natural beauty of Finland. The extensive use of wood speaks not only to Finland’s industrial production but also to its woodland heritage. The need to accommodate large crowds circulating through the building is helped by the offset placement of the entrance and exit, the “movement” of the wood, and the variegated light that bounces off the propellers. These elements work especially well in juxtaposition with the rectangular exterior. No one could possibly have expected such a free-flowing space to fit appropriately within a pre-made box building

In Architecture: from Prehistory to Post Modernism by Marvin Trachtenberg and Isabelle Hyman, Aalto’s works from the early 1920s through the 1930s are described as progressing from “Neoclassical Traditionalist Modernism”, to “High Modernism”, to “Counter-Modernism.”9 Juhani Pallasmaa describes his transformation as being from “Classicism to Rationalist Functionalism.”10 Aalto stands apart from the ‘Modern’ architects, who would certainly call themselves ‘Rational Functionalists’, in his treatment of the human. While Le Corbusier and Gropius were creating works for the “human machine” with geometrically rigid plans, sections, and elevations, Aalto was responding to the needs of man on a humanistic level, as a sensate and emotional being. At the New York Fair in particular, Aalto’s architecture reflects this aversion to man’s disconnect with nature by renouncing the “technological clarity of the International Style” as well as the “robotic consumer wonders of the Westinghouse and General Motors presentations.”11 Humans have very little in common with the factory-like buildings of the so-called “Modernists”. Concrete slab walls and steel pilotis simply do not bear the mark of human involvement or connection to nature that Aalto’s ergonomically-driven, curved wood forms evoke. Instead, Aalto aligns himself more with Frank Lloyd Wright, and architect who’s works always express “the limitations of the human being…there is always something which reminds us of the unknown depths of our being.”12

“Aalto was a realist. Rather than designing utopian architecture for machine-age mankind to be, he accepted flesh and blood humanity for what it was and built accordingly. Aalto’s buildings exist for no purpose other than human use. He carefully provides for human needs in buildings that are oriented toward what we would call “creature comforts,” not, however, in sybaritic excess, but in a restrained, high-minded manner…His clients were socialist-oriented inhabitants of a war-torn, thinly populated, Arctic land. Thus, his architecture proves typically Scandinavian in its sensitivity to basic human needs and in its socialist phobia of ostentatious luxury.”13

Logically, if Aalto builds according to the needs of humans their proportions, shapes and curves must certainly influence him. The Architect Kristian Gullichsen has thus proposed that Aalto’s wavy wall is based on the sensual curve of the hip:

“Aalto’s famous curving line…is usually interpreted as a metaphor for the shoreline of a Finnish lake. I think rather, that its origin is the human is the human body: it is the contour of the hip, so often used in painting, whether in a manner figurative or abstract, as, for example, the guitars of the cubist still lifes. Seen in this way, the origin of Aalto’s line is especially international. Several masters of modern art have used the free-form as a means of expression and the line that Aalto liked so much doesn’t have any mysterious meaning. It has clearly sensuous meaning and plays a precise role in the composition.”14

While the true formal inspiration for the curved wall of the 1939 pavilion was most likely the aurora borealis, other aspects certainly influenced its shape. The ebb and flow of the wall may have conjured subconscious images of a Finnish shoreline. Or perhaps the sensuous curves appeal to us on an instinctual level, one that Aalto admits to strongly considering. Or do Finnish woodlands inspire the shape? The most likely answer is that all these elements were considered and maybe more that are ineffable; locked within our unconscious and only triggered by experiencing the space. And yet there are still others who (whimsically) propose that Aalto created the undulation as an artistic signature for his masterwork. (The word aalto means “wave” in Finnish).15

Gullichsen maintains that Aalto’s curve is so obviously sensual that it that it lacks any mystery in its meaning. Freud would agree, citing not only the shape but also the many references to water, which for him signifies both the unconscious and (not surprisingly) sexuality. In fact though, while the curve may be sensual, it is precisely its mystery that makes it sensual in the first place. As an organizing element it partitions major elements of the exhibition creating unseen spaces that must be explored. From an architectural standpoint, it floats and cants over the central area in an odd but beautiful shape never previously seen in conventional architecture. If it represents the Northern Lights then it represents one of the most magical and mysterious natural phenomena on our planet. And even if it only represented a forest, this would carry huge significance if viewed through a Finnish lens. Finnish Architect Juhani Pallasmaa attempts to explain some of these associations:

“The forest was… a sphere for the imagination, peopled by the creatures of fairytale, fable, myth, and superstition. The forest was a subconscious sector of the Finnish mind, in which feelings of both safety and peace, fear and danger lay…While centuries have passed, and despite the introduction into Finland of industrial and post-industrial cultures, “the same symbolic and unconscious implications continue to live on in our minds, The memory of the protective embrace of woods and trees lies deep in the collective Finnish soul, even in this generation”16

The problem of summarizing a forest culture in a box-shaped building whose exterior could not be significantly modified led Aalto to bring the forest inside. Aalto’s forest theme could not have emerged so successfully in the New York Pavilion without his previous forays into pavilion design, both in Finland and in Paris at the World’s Fair of 1937. His Scandinavian style is typified in a forest exhibition in Lapua (1938), which makes the most out of the area’s natural materials. Unstripped pine saplings are bundled together to form columns and the interior is ingeniously sky-lit with evenly spaced slits subtracted from the wooden roof.

For Finland’s 1937 pavilion in Paris, Aalto covered his building with pinewood and birch to produce one of the most highly architecturally acclaimed experiences of the Fair. He took the motto “Le bois est en marche” (The wood is on the march) and used wood to merge his indoor and outdoor spaces, create pillars, define skylights, and determine every surface.

Aalto’s recently completed masterpiece the Villa Mairea (which was displayed as a model in New York) also aided his development towards the 1939 Pavilion, serving as a preliminary trial for a large curving wall to define space, and as further maturation of his forest theme.

The Finland Pavilion of 1939 is in many ways Aalto’s gesamkunstwerk. Aalto’s work had always incorporated natural materials and lighting effects but never before had one of his buildings evoked such a psychological and emotional response. The need to formally communicate the history and culture of an entire nation no doubt played a large part in achieving this effect. Aalto’s total control over the building, in its materials, structure, furniture, craft, and decoration, effectively made Alvar Aalto the representative for Finland. As such, Aalto felt the responsibility was his to create a humanistic architecture, designed to truly touch people in a meaningful and personal way and show the Finnish people as “tough and honest.”17 The challenge to create something subtle to explain Finland to the world while leaving a powerful image in the visitors mind seems paradoxical, but through the natural and mysterious forms inherent to Finland Aalto does just that.

–Thomas DeVoss